Fernando Peña

17 junio, 2009 Deja un comentario

PVA: Opinología rellenadora de huecos o empatía al borde de un ataque de nervios

22 enero, 2009 Deja un comentario

Donmar: http://www.donmarwarehouse.com; 0870 0606624 and http://www.donmarwestend.com; 0844 4825120

Haymarket: http://www.trh.co.uk; 0845 4811870

Duke of York’s: http://www.aviewfromthebridge.co.uk; 0870 0606623

Trafalgar Studio: http://www.theambassadors.com; 0870 0606632

Young Vic: http://www.youngvic.org; 020-7928 6363

Apollo: http://www.threedaysofrain; 0844 4124658

Gielgud: http://www.gielgud-theatre.com; 0844 4825130

Globe: http://www.shakespeares-globe.org; 020-7401 9919

Novello: http://www.novellotheatre.com; 0844 4825135

Courtyard, Stratford: http://www.rsc.org.uk; 0844 8001110

Birmingham Rep: http://www.birmingham-rep.co.uk; 0121-236 4455

West Yorkshire Playhouse: http://www.wyp.org.uk; 0113-213 7700

Tobacco Company, Bristol: http://www.tobaccofactory.com; 0117-902 0344

Royal Exchange, Manchester: http://www.royalexchange.co.uk; 0161-833 9833

Nottingham Playhouse: http://www.nottinghamplayhouse.co.uk; 0115-941 9419

Noel Coward: http://www.officiallondontheatre.co.uk; 0844 4825141

Lyric, Hammersmith: http://www.lyric.co.uk; 0871 2211729

Palace: http://www.priscillathemusical.com; 0844 7550016

London Palladium: http://www.officiallondontheatre.co.uk; 0871 2970748

22 enero, 2009 1 comentario

Are their brains bigger than ours? In a public discussion held at New York’s Columbia University this month, the RSC’s Michael Boyd and Dr Oliver Sacks compared notes

[..p..]

Watch the Columbia University talk here

http://qtss.cc.columbia.edu/wlf/sacks_boyd.mov

Michael Boyd: We worked with about 30 actors over nearly three years on the RSC’s last complete cycle of the history plays. All the actors were in at least seven of those plays and learnt a huge number of roles. Halfway through the project, we left the first four plays behind for nearly a year. And we had to revive them. The actors began to get anxious about whether they would remember them: not only their principal roles, but the roles they understudied – thousands of lines, hundreds of states of emotions. An extraordinary feat of spatial memory was required, too: they had to remember where to go. Where am I? Backstage or front of house?

This process started with actors on their own going through their lines. They didn’t remember them. We then moved on to working together in a room, sitting down doing a line-run. It wasn’t very good. Then we decided to cut to the chase and just fling all four plays onto the stage – without costume, without décor, without all the effects. And the actors were very nearly word-perfect straightaway. It was clear that what they were trying to retrieve was no more than a broken bit of memory, only complete when the actions of their bodies and the emotions were combined together with the recall of the line. And there was a further improvement when they were not only together on stage, but also together with an audience. Then they became absolutely pitch-perfect and word-perfect, with an urgent need to communicate. I think that says something about where we keep our memory. Maybe our memory is in our body as well as in our cranium.

It goes side by side with something I just came across. I was invited to the Royal Academy to talk about space, on a panel that included a neurologist. I was galvanised by his account of some research he’d done on London taxi drivers that examined their hippocampi – the part of the brain associated with memory. Not only were their hippocampi unusually enlarged after taking the Knowledge, and further enlarged after a year or so of actually doing it, it was again clear that these taxi drivers remembered places and destinations through the physical sense of turning left and turning right.

They could not remember where a street was unless they “physicalised” mentally the journey to that street. So this neurologist was interested in our sense of space being an important part of the process of how we remember.

Oliver Sacks: These are very important observations, and they’re not the sort neurologists and neuroscientists are usually privy to. We tend to see solitary individuals who may have memory problems of one sort or another.

Now, although my colleague dwelt on the hippocampus as a prerequisite for a particular sort of memory, the hippocampus certainly is not sufficient – many other parts of the brain would be involved. I see quite a lot of people whose hippocampi have been destroyed, by disease or by accident. And one speaks of these people as having amnesia, and if one is amnesic one may forget events within a few seconds. One may also lose events from one’s own past. One may lose one’s entire autobiography and a great deal of general knowledge. But one does not lose the ability to act or to perform.

I have written about a striking example of this with a musician and musicologist, Clive Wearing, who had his hippocampus systems wiped out by an encephalitis 20 years ago. He can’t remember anything much for more than seven seconds. But this man is able to conduct a choir, conduct an orchestra, play the piano or sing long, complex pieces of music. His abilities to perform musically are entirely spared. If you ask him in terms of knowledge, “Do you know such and such a Bach prelude and fugue?”, he will look blank or say no. But put his hands on the piano, sing the first note and he’s off.

And this sort of preservation of procedural memory may apply not only to music. I know an eminent actor who has also had damage to his hippocampi and has lost the memory of much of his past. But all of his acting skills, all his enormous repertoire, from Euripides to Beckett, is all there. So the sort of memory that is involved in acting involves much more of the brain than just the hippocampi.

Chairman: Do actors deliberately try not to remember in the ordinary ways, in order to do acting better?

MB: Yes. There is definitely a moment for every creative artist when there is loss of self. It’s not even just creative artists.

I think everyone can remember those moments when you are “in the zone”, when you’re not aware of what you’re doing, when you’re not consciously trying to recall what you should be doing, you are simply in the act of doing it. Chairman:So, Michael is about to do these eight plays, and he has the same group of people. Is there anything you would tell him, Oliver, that neuroscience would say, “watch out for”?

OS: What strikes me is the thousands and thousands of lines on the one hand, and roles on the other. These lines would have no coherence, would make no sense, would not hold together without a role, and especially a role in relation to other roles. The ability to enter a role can again outlast the hippocampi. It can outlast all sorts of mental abilities.

I see a lot of people with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. I had a cousin, an actress and especially a Shakespearian actress, who became quite demented, but one could give her a line from almost any speech or sonnet from Shakespeare and she would continue it, and not in a mechanical way, but apparently with all her own feeling. Or she would take on a role like King Lear or Hamlet. This business of a role, I think, is essential to the sort of memory you’re describing.

MB: I think good performers tend to be very open, to the point where they get dismissed as sentimental creatures – there’s this horrible, contemptuous term “luvvie” used about the theatre. But I do think there’s something missing in an actor’s persona, or maybe mind, about censoring out certain emotions. They are “overreceptive”, and that can be troubling for them in their lives. People who are tremendously good at closing out the troublesome tend not to be brilliant performers.

There’s a valve in a brilliant actor that is “deficient”. They’re good at embodying emotion, but they’re not very good at shutting it out. I think that’s why there is something inherently unstable about the condition of being an actor that’s also creative. Brilliant actors who survive to have a career manage that “deficiency” extremely well and lead perfectly normal lives. I don’t want to discourage anyone from joining the profession . . .

OS: Are you saying that many or most actors may react, even when they’re not in role or on the stage, too extravagantly, too directly, too uninhibitedly?

MB: No – I think that’s a caricature – but they have to carry around emotion. Musicians I know say they can’t get music out of their heads. And actors can’t get emotions and stories out of their heads.

OS: Let’s connect this with embodiment. I watched De Niro and Robin Williams when they were taking on characters from Awakenings [the 1990 film about his work]. In particular with De Niro, sometimes when we had dinner after a day’s filming, I would observe that his foot was turned inwards, or that he had some postures which belonged to Leonard L, the character he’d been portraying and embodying, and these fragments were still in him. I actually got a little frightened of the literalness of embodiment with him. Somehow he seemed to be becoming too much like Leonard L, and I feared Leonard L might be taking over.

On one occasion he asked me to advise him a little bit on how people with Parkinsonism might fall if they had no postural reflexes. And in the middle of my explanation, just as I said that such people might fall heavily backwards without warning, he fell heavily backwards – on me. And at that moment I thought: he’s not acting, he’s got it. He’s actually become Parkinsonian through acting it so well.

MB: Yet another way of addressing this is for an actor to be powerfully suggestive. That’s quite an important part of the process.

OS: Well, we all have that. We flinch when someone else receives a blow, and neurologists have started to talk about “mirror neurones” in the brain, which make spontaneous representations of what is happening with other people, so you then feel these yourself. And it’s thought that the basis of sympathy – and, to some extent, imitation and incarnation – is partly due to these mirror neurones.

I think there are different levels of representation. Now, for example, with Robin Williams [who played Sacks in Awakenings], there were two clearly distinct stages. Before the filming, we went around together and he was charming, genial and brilliant. It didn’t occur to me that he was, in fact, observing me minutely. About three weeks later, we’d got into a conversation in the street, and I’d got into what I’m told is one of my characteristic pensive postures. I saw Robin was in exactly the same posture, and I had an instant feeling he was mirroring me. I then realised he was not doing so,but he had acquired and embodied my gestures, my postures, my so-called tricks of speech and idiosyncrasies. And it was startling, like suddenly having a younger twin.

Audience Q: Do you find method acting useful in your work?

OS: Method acting is acting from the inside out? Is it?

MB: Yes, it’s an attempt to.

OS: I had thought De Niro was a method actor, but I once asked him about acting and he gave me a three-word answer. He said, “I observe behaviours.” And I said, “Yes, but what about the character, the Richard III-ness or whatever?” And he simply repeated himself. He said he observed behaviours and felt if he got them sufficiently, that would embody the inwardness. That was, I guess, outside in.

Audience Q: You gave the example of when you sat around with your actors and tried to get them to remember their lines first, versus physically going through the motions. What’s the difference between a speech act and a physical embodied act?

MB: Speech is the most physically intimate act possible. It comes from the wet bits inside you. The air I’m using is coming from way down inside, even though I’ve got bad posture, and just the pure boring business of retrieving these lines is hard to do when you are not engaged in the entire act. I would say they are best unseparated.

OS: I imagine it’s similar with music in a way – although you have to learn the notes first, you then have to forget the notes to play the music. Otherwise you remain a virtuoso, and not a musician.

Michael Boyd is artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company; Oliver Sacks MD is professor of neurology and psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center, NYC. The discussion was chaired by Lee C Bollinger, president of Columbia University

http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/stage/theatre/article5196960.ece

15 agosto, 2008 1 comentario

Queridos amigos,

Cortito nomás.

Como algunos de ustedes saben, o por rumores de la prensa sensacionalista que no para de acosarme… Carlitosway participó por vez primera en una obra de teatro y fue EL HITO que faltaba en la vida de alguien que se jacta de que le gusta el teatro.

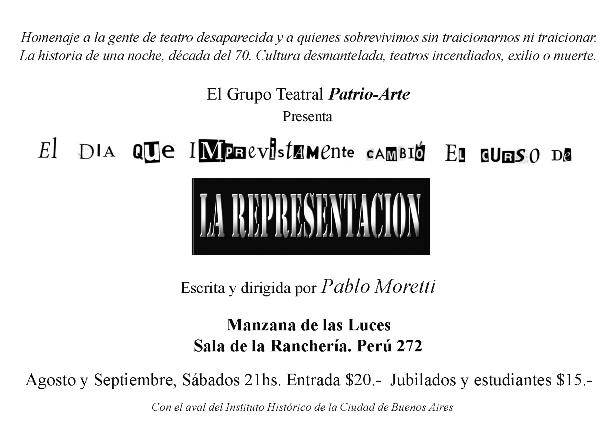

Mi papel es muy chiquito pero muy interesante, y el día del estreno me sentí muy bien. La obra se llama El Día que Imprevistamente Cambió el Curso de la Representación y se está poniendo en “La Manzana de las Luces”, tugurio digno de verse si lo hay, durante todo agosto y septiembre.

La verdad es que tengo la suerte de estar mezclado con este grupo tan lindo, el director es un artista de cepa, y estoy aprendiendo horrores.

Simplemente quería compartir con uds. esta noticia y, por supuesto, a los que les interese y sin compromisos, me va a poner muy contento verlos.

Un beso grande. -CS-

PD Les paso la ficha para que vean, lamentablemente no tenemos invitaciones ni descuentos.

PD2 Obvio que pueden venir con quien quieran y/o reenviar la info a quien crean que pueda interesarle.

PD3 Creo que llamando y estando un rato antes en boletería se pueden arreglar con la entrada.

PD4, basta de PD’s

El Día que Imprevistamente Cambió el Curso de la Representación

18 abril, 2007 Deja un comentario

ENTRENAMIENTO ACTORAL

Coordinación:

RUBÉN SZUCHMACHER y PABLO CARAMELO

Destinado a estudiantes de teatro avanzados y actores

Temas:

El texto como materia. Correspondencia texto- cuerpo – pensamiento.

La acción en la palabra.

La forma de la palabra y su ritmo.

Entrenamiento con textos de Tragedia Griega y Siglo de Oro Español.

Durante este cuatrimestre se trabajará principalmente textos de Federico García Lorca

http://elkafkaespacioteatral.blogspot.com/2006/12/rubn-szuchmacher-talleres-y-seminarios.html

——

* Manos, palmas hacia afuera, brazos a la altura de hombros, relajar hombros y respirar.

* Idem anterior, bajando y expirando y subiendo aspirando.

* Cadera,

subir y bajar los brazos, en circulos, de derecha a izquierda

de atrás hacia adelante

* Agachado, piernas un poco flexionadas, puños, respirar

* Idem anterior, + recostarse y levantarse todo los mov. a la vez.

* Pelvis

* Rodillas

* Tobillos, sacudir

círculos

* Centrífugos, brazos sueltos

* Expirar con labios sueltos, temblando

con ‘eme’ y con ‘aaa’, etc

* Movimientos de mandíbula

* Masaje Cara

* Boca

17 noviembre, 2006 Deja un comentario

Estrena SABADO (SAB. 18/11), CASONA DE HUMAHUCA A LAS 22 HS.

13 noviembre, 2006 Deja un comentario

UADE – Elenco Estable

Dirección: Patricia Pisani

Contacto: csims@plazaatsensus.com.ar

U.A.D.E. (LIMA 717) // los sábados 11 y 18 y los domingos 12 y 19 de Noviembre. A las 20.30hs.

13 noviembre, 2006 Deja un comentario

Con Magalí Melia & Cecilia Bruza

Próximo estreno en La Tertulia

De Javier Daulte

Fecha de estreno: 18 de Noviembre

Sábados a las 23 hrs.

Dirección y puesta en escena: Martín Ortiz

2006: 5 funciones hasta el 16/12

http://www.mundoteatral.com.ar/ar/teatr … hp?uid=316

http://www.paginadigital.com.ar/pagbases/teatro_amp.asp?Id=1163531209

http://www.lanacion.com.ar/entretenimientos/cartelera/obraFicha.asp?obra=7462&teatro_id=744

http://www.alternativateatral.com/ficha_obra.asp?codigo_obra=7197

31 agosto, 2006 Deja un comentario

Clarín:

Espectáculos

CINE : ENTREVISTA CON ENRIQUE PIÑEYRO

«Pretendo que mi película cambie algo»

Mañana, en el séptimo aniversario de la tragedia de LAPA, llega a los cines «Fuerza Aérea Sociedad Anónima», en la que el director de «Whisky Romeo Zulú» se centra en los riesgos de volar en la Argentina.

Miguel Frías

mfrias@clarin.com

Enrique Piñeyro es una rara avis en cualquier firmamento; «un conflictuado vocacional que termina todas las carreras.» Médico sin consultorio, piloto sin avión —renunció a LAPA, en desacuerdo con la política de seguridad, un par de meses antes del accidente del 31 de agosto de 1999, en el que murieron 67 personas—, ex miembro del gremio de pilotos (APLA), actor inesperado (Garage Olimpo, Esperando al Mesías, Nordeste), productor de cine, director de películas que esgrime como armas de francotirador; aunque se defina, por su falta de formación, como un «analfabeto cinematográfico».

Su opera prima fue Whisky Romeo Zulú, recreación ficcional del proceso que terminó con un Boeing 737 de LAPA estrellado en aeroparque. Fuerza Aérea S.A., su segundo filme, que se estrena mañana —en un nuevo aniversario de aquella tragedia—, es un documental didáctico y escalofriante sobre la inseguridad aérea en la Argentina. Las escenas —y grabaciones— más shockeantes fueron obtenidas con cámaras ocultas en la torre de control de Ezeiza: radares que se plantan, operadores que dan indicaciones erróneas por no dominar el inglés, técnicos confundidos al afrontar emergencias, infracciones, un misilazo que casi baja un avión de pasajeros…

¿Por qué decidiste retomar un tema cambiando el formato cinematográfico?

Porque nada cambió: la Fuerza Aérea sigue teniendo el control sobre la aviación civil, «privilegio» que compartimos con Nigeria. El documental me permitió tener una contundencia imposible de lograr en la ficción. Whisky… instaló el tema, transmitió emoción y reconstruyó la previa al accidente de LAPA. En Fuerza Aérea S.A. muestro el acá y ahora: esta noche te subís a un avión y vas a estar a merced de todo lo que se ve en pantalla. Este material es inapelable; estoy harto de la negación psicótica de la Fuerza Aérea.

Esta película demuestra que hasta los fóbicos y los paranoicos a veces tiene razón…

Sé que la película impacta. Los que no vieron Whisky… por miedo a volar se quedarían paralizados con Fuerza Aérea…. Pero somos grandes: lo mejor es afrontar las deficiencias y evitar catástrofes absolutamente previsibles. La solución no es dejar de volar: viajar en micro es más peligroso. Hay que ser sensatos: tenemos terror de morir en un robo o en un secuestro extorsivo, pero hay muchísimas más posibilidades de que nos matemos en un accidente de tránsito, que suele ser tomado como parte de una cotidianeidad inevitable. En este punto, somos Irak.

Renunciaste a un trabajo que te apasionaba, confrontás con la Fuerza Aérea. ¿Qué te lleva a meterte en problemas?

Cada uno debe responder a lo que la vida le pone enfrente. A mí me puso un accidente en cámara lenta. Vi el proceso entero que llevó a la muerte a 67 personas, y no por poderes de clarividencia. Aunque creo que agoté los medios de denuncia, no dejo de preguntarme si realmente hice lo suficiente. No quiero volver a preguntármelo.

¿Pero por qué saliste vos a hacer denuncias y no otro piloto? ¿Por tu capacidad económica? ¿Por agallas?

No me voy a hacer el héroe y decir que si no tuviera plata lo habría hecho igual. Por otro lado, abandoné mi mayor pasión: volar. La mayoría de los pilotos no tiene el respaldo económico para hacer lo que yo hice. Otros lo tienen y no hacen nada… Pero no se le puede pedir a todo el mundo que ponga la cara por lo que el Estado no hace. Yo siento que me tocó este destino. Preferiría ser piloto de Air France y volar hacia la Polinesia sin pelearme con nadie. Nunca imaginé que iba a terminar así.

¿Es cierto que luego de una reciente solicitada tuya denunciando hostigamientos militares tuviste una reunión con la ministro de Defensa, Nilda Garré?

Sí, estuve dos horas con ella. Le dejé la película y le manifesté mi preocupación, que, en el fondo, es o debería ser la de todos. Los que volamos en avión tenemos un problema grave: usamos un medio de transporte gestionado por una autoridad incompetente, no profesional, corrupta. Si nadie hace nada, Fuerza Aérea S.A. va a ser el documental del próximo accidente.

Impresionan las imágenes tomadas con cámaras ocultas. Que hayas logrado meter una cámara en la torre de control ya es una muestra de inseguridad…

Estos «fenómenos» hacen inteligencia interna pero descuidan la seguridad más elemental. Son incompetentes. Me investigan a mí y yo hago lo que quiero en los aeropuertos. Primero hice un largometraje en 35 milímetros. Y ahora logré filmar la torre de control y la sala de radar. Al Qaeda se haría un festín con ellos.

¿Cómo conseguiste el material?

Es «top secret». Sólo te puedo decir que al no haber canales de queja normales me transformo en receptor de todas las denuncias. Como todos saben que estoy dispuesto a ventilarlas, me las dan a mí. En una sociedad normal esas denuncias irían por otros carriles; no soy funcionario judicial ni parte del sistema de control de la aviación civil.

En la película, la torre de control parece una oficina pública de sketch de Gasalla, con empleados indolentes…

Es patético. Pero la culpa no es de los operadores que aparecen, porque los pobres tipos no tiene capacitación, les pagan sueldos de hambre, los someten a sobreturnos, les escatiman vacaciones, les pagan el presentismo en negro, no los dejan ascender. El tema es que han aplastado a los que trabajan en control aéreo; el último curso de inglés fraseológico se los dieron hace seis años. En la película queda claro que los operadores no saben comunicarse con los pilotos extranjeros.

En tus dos filmes aparecés como protagonista; en el segundo como conductor del relato. ¿No es un exceso de personalismo?

No. Era lo que necesitaban los productos. En Whisky… lo ideal era que un piloto actuara de piloto. Y en Fuerza Aérea S.A. había que hacer una decodificación del lenguaje técnico aeronáutico. La aviación es un tema complejo y más cuando quieren oscurecerlo para ocultar irregularidades. Tengo la capacidad para volver transparente lo que quiero contar: tenía que hacerlo yo, necesariamente.

En la película se muestra la convicción del director, basada en registros contundentes, pero no distintos puntos de vista, excepto a través de antiguos programas televisivos. Ese estilo, que remite a Michael Moore, ¿no cierra el debate?

Saliendo del Lincoln Center, una mujer me dijo: «Usted es el Demi Moore argentino» (ríe) y yo le respondí que mis pechos eran naturales. Es cierto: procuré que no hubiera espacio para la discusión. No quiero más instancias de debate, que ya las hubo en cantidad, sino cambios en una situación que nos lleva a otra tragedia. ¿Qué van a decir ahora? ¿Que es fantasía el misilazo? ¿Que es mentira que los operadores de la torre no entienden inglés? ¿Que miento al denunciar que los radares no funcionan?

¿Es cierto que no tenés una gran formación en cine?

Entramos en la parte de autoflagelación del reportaje. Siempre temo que me pregunten por las influencias de determinado director. Fui un espectador entusiasta de películas hasta los quince años, pero mi sueño era ser piloto y jamás imaginé que terminaría dirigiendo. Vi y veo poco cine. No puedo identificarme con corrientes o directores. Hice, hasta ahora, películas «con propósito», basado en el tema más legítimo que tenía para contar, con la intención de mejorar las cosas, pero sin formación académica. Lamentablemente soy un analfabeto cinematográfico; aprendo sobre la marcha.

¿Cambiará algo con «Fuerza Aérea…»?

Ojalá que sí. Tiene imágenes irrebatibles, en un formato persistente, que no tiene la futilidad de un programa televisivo. Si hubiera hecho un trabajo para TV, lo vería más gente. Pero terminaría siendo el escándalo del miércoles a la noche, del que se habla el jueves a la mañana y se olvida el fin de semana. Pretendo que mi película cambie algo, que no sea la anticipación de otra tragedia. Tengo un hijo de dos años y medio que algún día va a volar como pasajero o piloto. No quiero que lo haga como nosotros hoy. Sería un delirio.

—–

Enrique Piñeyro, esta vez con un documental

Llega «Fuerza Aérea Sociedad Anónima»

Hay momentos en que los registros con cámara indiscreta usados por Enrique Piñeyro para su documental «Fuerza Aérea Sociedad Anónima» se parecen a las parodias de «El show de Benny Hill». Otros a los gags de «Y dónde está el piloto » Pero no, no se trata de una humorada sino de un tema muy serio, del que dependen tantas personas como las que viajan en aviones que sobrevuelan la Argentina, todos los días. Piñeyro piensa que después de los trágicos accidentes de Austral en Fray Bentos, Uruguay, y el de Lapa, en el Aeroparque Jorge Newbery la gente no debería estar tan segura acerca de la aeronavegación local. Desde su multiplicidad -médico especialista en el tema aeronavegación, piloto, actor y director cinematográfico- se encargó de denunciar una y otra vez qué es lo que pone en peligro de muerte a las miles de personas, argentinos y extranjeros que suben o bajan de un avión en cualquier aeropuerto con nuestra bandera celeste y blanca.

La tarea de Piñeyro como director de cine comenzó hace dos años con «Whisky Romeo Zulu», que reconstruyó su propia experiencia como piloto civil en Lapa y los hechos que precedieron al accidente ocurrido en la Costanera Norte en 1999, cuando un Boeing 737-200 salió de pista, atravesó la calle para terminar chocando contra un terraplén a pocos metros de una estación de combustible, con un saldo de 65 muertos. Piñeyro asegura que una de las principales causas de lo ocurrido es la corrupción que, insiste, compromete al alto mando de la Fuerza Aérea, que tiene la responsabilidad de controlar a la aviación civil y comercial en todo el país. Sobre esas reiteradas denuncias y con unas cuantas pruebas elocuentes entre sus manos, hizo un documental que la productora Aquafilms estrena mañana.

-¿Cuál es tu meta?

-Que el sistema cambie. Mi carrera no se desarrolló como pensaba cuando era chico. A mí la vida me puso en una situación un poco extraña respecto de eso. Cuando vos ves que se va a matar un montón de gente, hacés lo imposible por decirlo a los cuatro vientos.

Lo peor de todo es que ya conté esta historia, y no se modificó el sistema: sigue en manos de la Fuerza Aérea. Lo que estamos haciendo con este documental es un anticipo del próximo accidente.

-¿En los aeropuertos argentinos se tiene demasiada suerte?

-Sí. Todos los días hay aviones que no tienen separación provista por el control. Todos los días hay lo que los controladores llaman «un palo», que es cuando los aviones pierden la separación que les dio el control, por lo que fuera. Que choquen dos aviones en el aire es una cuestión de tiempo, nada más. Si siguen volando así, se lo van a pegar. No es que sea una obsesión, sino que tengo la responsabilidad de hacerlo público, para que la opinión pública sepa cómo la están estafando y para que los gobernantes sepan de la urgencia que esto tiene. No es que tengan dudas de que hay que hacerlo, pero tal vez no tienen la clara conciencia de lo urgente que es.

-¿Qué piensan las aerolíneas extranjeras de esta situación?

-Normalmente, los que la pasan mal son los pilotos extranjeros, porque los de acá son rebichos , no le creen nada a nadie. No creen estar realmente separados por radar. Están mirando para todos lados, escuchando todo. Alguna vez me han mandado un punto de notificación con la misma altura, a la misma hora, de otro avión que yo venía escuchando. Le digo: «Escúcheme Baires, ¿no está mandando dos aviones al mismo punto, a la misma hora y nivel?». «Ah sí «, te dicen, mientras te das vuelta y lo tenés ahí a cien metros. Al día siguiente me pasó lo mismo, en el mismo punto.

-¿Siempre fue así?

-Está empeorando. Siempre fue malo, porque te puedo hablar de episodios de hace diez o quince años. La Fuerza Aérea siempre fue corrupta, pero en el pico de descontrol del 97 al 99, 142 personas muertas con los niveles de tráfico aéreo que tenemos es un disparate, nos catapulta a los últimos lugares del planeta, muy por debajo de la mayoría de los países africanos, sin hambrunas, sequías ni guerras tribales. Cómo será que en dos años se muere más gente que en los veintisiete que preceden. He oído decir a jefes de la Fuerza Aérea que «accidentes hay en todos lados». Sí, los hay, pero no por corrupción, como hay acá. Habilitar mal un avión, falsificar faxes internos, lograr dispensas de entrenamiento a pilotos para ahorrar plata, no dar vacaciones y que a un piloto se lo califique para comandante cuando estaba bochado en el simulador, todo eso es delictivo.

-Si las empresas internacionales exigieran seguridad, ¿cambiaría la cosa?

-Cambiaría, pero no lo van a hacer porque ahí manda el negocio. A partir de la desregulación, la aviación pasa a ser una variable más de mercado. Lo que han logrado hacer es quebrar a los operadores tradicionales, como PanAm, Eastern, Swissair, Varig, Alitalia va a quebrar, y traspasar toda esa fuerza laboral de alto costo al low cost recontratada por la mitad o la cuarta parte del sueldo. Además de bajar costos, deterioraron la seguridad. No jodan: es un servicio esencial, lo que mantiene la rueda de la economía funcionando.

-Cuando la gente vea esta película también se va a asustar

-Sí, pero es una angustia-señal, no es automática, tiene un fundamento claro. Lamento ser el portador de este mensaje. El primer paso para solucionar un problema es aceptar que lo tenemos; si no, vamos a seguir jugando a que estamos en el Primer Mundo. Decimos «¡pobres los africanos!», pero ellos están volando más seguros que nosotros.

-¿Quién debería ocuparse?

-Una agencia de seguridad integrada por profesionales, no como acá, donde los controladores son el último orejón del tarro. Les pagan mil pesos a tipos que tienen diez aviones a su cargo. No pueden progresar nunca y encima tienen que ser personal civil o militar de la Fuerza Aérea. Toda la faja dirigente son estos alegres payasos que de ser tenientes troperos pasan a sala de radar. Si al que le toca es inteligente, ceba mate y no se mete. Si tiene un coeficiente intelectual bajo, como la gran mayoría, viene con nuevas normativas.

-¿Todos piensan igual en la Fuerza Aérea?

-Hay muchos jóvenes oficiales que vinieron a ver «Whisky Romeo Zulu» y que en los debates posteriores se identificaban y decían con qué estaban de acuerdo o no, de un modo argumentado y democrático. Vayan a preguntarle al brigadier Carlos Matiak (actual comandante de Regiones Aéreas) si se atreve a hacerlo. Estos pibes quieren volar en una Fuerza Aérea de la cual sentirse orgullosos. Pero hay que hacer algo, porque si terminan transformándose en capitanes o brigadieres como los de ahora, estamos listos.

+ info: http://www.aquafilms.com.ar/